Neluka Silva and Lilani Dias

Introduction

Since Independence, mainstream Sinhala cinema has been regarded as a popular form of entertainment in Sri Lanka, more sensitive than any other form of art to the fluctuations in the socio-political landscape. While identifying it as a widely popular mode of cultural practice, Jayadeva Uyangoda unveils the explicitly political character of Sinhala cinema. “Its backdrop was the consolidation of a post-colonial nation, particularly from the mid-fifties onwards, with a strong emphasis on cultural protection” (38). Jayasinghe and Dissanayake (2008) argue that “the cinematographic heritage acquired during six decades of filmmaking bears witness to the development of Sri Lanka’s identity and nationhood” (45). In Sri Lanka, the stark reality of the country is exposed through its cinema whenever possible. Moreover, the cinematographic heritage acquired during six decades of filmmaking bears witness to the development of Sri Lanka’s identity and nationhood (45).

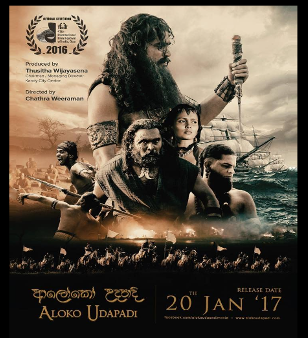

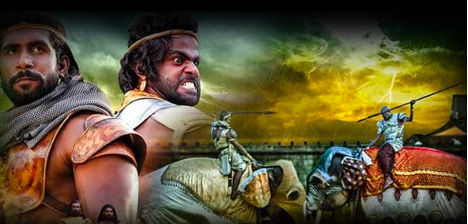

This paper explores the construction of a dominant Sinhala Buddhist identity in two popular recent mainstream historical films – Maharaja Gemunu (2015) and Aloko Udapadi (2017) through their narrative strategies and cinematographic representations. The plots reveal that the configurations of ethnicity, in relation to the non-Sinhala characters, are problematically constructed. The Sinhala Buddhist identity is cast as diametrically opposed to the Chola invaders from India. It is further bolstered through the interweaving of religion as the legitimising discourse. The non-Buddhist is cast as malicious and barbaric: from the Nigantha priest who alerts the Cholas about the King’s escape in Aloko Udapadi to King Elara in Maharaja Gemunu and their soldiers. The Chola invasions are rendered as a direct threat to Buddhism: The significant decision to write down the Tripitaka, thereby documenting the Dhamma is the result of the direct threats to life experienced by the monks in Aloko Udapadi. Similarly in Maharaja Gemunu, King Dutugemunu wages war in the name of safeguarding dhamma. In this manner, throughout the films, we encounter Buddhist monks who transgress their traditional religious role.

Cinema

Cinema, in general, being a medium of communication catering to all strata of society, irrespective of their levels of education, is an extremely powerful tool in informing and influencing the general public (Jayasinghe and Dissanayake 45). As a dominant form of cultural production, it cannot be considered to operate solely as a form of entertainment, but developing Benedict Anderson’s work on the role of culture in creating a shared emotional space in Imagined Community, its potency lies in creating the illusion of “reality” in the collective imagination and thereby becomes instrumental in mobilising and influencing the citizens of a nation to perceive, operate and conduct themselves in a particular manner that helps create the archetypal ‘nation’ or fraternity. Dissanayake observes that in Asia the interconnections between cinema and nationhood are intimate and complex, since “it constitutes a very powerful cultural practice and social institution that both reflects and inflects the discourse of nationhood” (para 2). Cinema portrays the uniqueness of a given nation when compared to other nations (Dissanayake xiii).

Cinema continued to demonstrate strong political and ideological ties to the dominant State Apparatus through predominantly projecting and reflecting idealised models of identity and ideology. Often the idealised images often gain more force when contrasted with a less-than-desirable Other who has an alternative or threatening ideology, identity, or desire. The manner in which certain identities and subjectivities perform within narratives helps to reproduce and reassert the rewards of being a good citizen whilst concomitantly projecting the perils of being ideologically subversive (Cheung and Fleming 5).

Mainstream Sinhala Cinema in the post-war Era

The victory of the Sinhala State against the LTTE in 2009 rekindled the historical genre in Sinhala cinema, foisting renewed interest in bolstering nationalism. In his appraisal of mainstream Sinhala cinema, Uyangoda foregrounds this nexus, saying “Sinhala nationalism has been the crucial ideological terrain within which political and cultural responses to cinema have been located. It has been the fate of the cinema, and the visual medium in general, to suffer the consequences of violent passions whenever Sinhala nationalism came to the centre of social and political conflict” (41-42).

“The official end of the war coincides with the beginning of a markedly changed Sri Lankan cinematic aesthetic, with a boom in ‘patriotic’ film productions”[1] (Karunanayake and Waradas 2). Patriotism, in recent historical films, is overlaid with a rhetoric that visually renders the glory of state-sanctioned Sinhala Buddhism. They provide a potent space to reinstate a particular type of identity that effaces historical, cultural, linguistic, and religious ties undermining the rhetoric of reconciliation. The correlation between State sponsorship and Buddhist institutions and/or Buddhist clergy for the historical films is striking. If the principal agenda is to provide historical “insight” and “accuracy” (as espoused in publicity material), we need to confront the question “whose insight and whose version of history is projected onto the wide screen?” In post-2009 historical films, non-Buddhist “outsiders” or “others” (often posited as violent aggressors) are framed as a threat to the Sinhala Buddhist identity and legacy. Their demonisation, even within the parameters of the film, is validated by Buddhist clergy. The historical genre becomes critical in providing the rationale for identity politics.

The Historical Genre and the Re-assertion of Sinhala Hegemony

The historical film is theorised as intricately aligned with dominant national narratives. Among its functions – “… document and fiction, … reason and emotion, scholarship and art, a public and a commercial enterprise” (Rosenstone and Parvulescu 7), it plays “an essential part of a process of defining nations” (Williams 4). The historical ‘fiction film’, argues Mead, is imperative in “reflect[ing] the “national character” of the nation” (qtd. in Williams 8). It can be deployed to become a conduit for promoting national values (Rosenstone and Parvulescu 4-5), since the plot centres on ‘real’ or imagined/revised historical events, to create a nostalgic setting (Davis qtd. in Rosenstone and Parvulescu 3). The nostalgic setting fulfills the yearning for a halcyonic past that reinforces the glorification and mythologization of legends of the heroism of the dominant group. In the case of the plot that traces events of the distant past, blurring of historical accuracy/details, and unreliability, are accepted as inevitable within the genre. Wimal Dissanayake observes that the interconnections between cinema and nationhood “constitutes a very powerful cultural practice and social institution that both reflects and inflects the discourse of nationhood and is “imbricated with national myth-making and ideological production” (Dissanayake xiii) Jean-Luc Comolli and Jean Narboni (1999, 754) argue that cinema—as a product of the economic and ideological system—also inadvertently reproduces its own conditions. Indeed, “every film is political, in as much as it is determined by the ideology which produces it (or within which it is produced, which stems from the same thing)” (ibid.; italics in original).

These two historical films selected, garnered immense audience appeal for their depiction of significant “historical events” that have been ingrained in the popular imagination. Furthermore, they reflect dominant thematic preoccupations evident in the post-war historical Sinhala film. The reassertion of the entwined role of religion with politics is evoked in both films through constructions that indicate the historical loyalty of the ruler’s subjects towards protecting and sustaining Buddhism. The cinematic narrative of both Maharaja Gemunu and Aloko Udapadi refers to the state’s political administration as one that is inherently dependent on the welcome intervention of Buddhist ideologies. The advisory role of the Sinhala Buddhist monks in the Sinhala Buddhist King’s actions to quell the invading non-Buddhist “Other” resonates with the increasingly evident role Buddhist monks play in Sri Lanka’s political arena following the 30 years of war against the LTTE.

Maharaja Gemunu

Maharaja Gemunu cinematically depicts the story of King Dutugemunu (101-77 BC), who defeated King Elara, a Chola invader from South India, who had seized power and ruled the country for forty-four years. The film depicts Elara, as a former soldier and spy under King Kharawela of Kalinga, the ruler of the Southern Kingdoms of India during the second century BC. Elara arrived on the Island of Lankadveepa, acting as a naval chief, with the motive of occupying the territory and threatening the sovereignty of the Kingdom. Though he wrested power in the north, he was preoccupied with King Devanampiyatissa’s prophecy that a King named Gamani Abhaya (Dutu Gemunu) would secure the Kingdom of Rajarata and build a pagoda (dageba) at its centre. King Gamani Abhaya deployed strategies to overcome the tactics of Elara. In the film, after protracted battles, the final battle depicts Elara and Gamini Abhaya engaging in face-to-face combat, resulting in the death of the former. In the final scenes, when Elara lies dying in Dutugemunu’s arms, there is an attempt to portray the Chola king in a positive light as Elara acknowledges Dutugemunu’s virtues and admires his skills. His concern for the plight of his people “… these people followed me because they believed in me, please don’t harm their gods, their beliefs and way of life”, is counteracted by Dutugemunu’s reassurance: “nothing will happen to your people. Their Gods will not be destroyed. I am going to build a stupa here to convey two messages that I respect you and if I can respect you, then my people should also respect your people.”

The film interweaves all the elements of a mega-blockbuster with romance and intrigue, and magnificent battle scenes replete with violence, blood, and gore. Underlying sensationalism is the sombre undertones of the Dhamma (the philosophy or undistorted truth that the Buddha taught). The inextricable link between religion and politics is captured in the opening scenes.

Sumana Saamanera (A junior monk) who appears to be in a comatose state is surrounded by an assembly of maroon-robe-clad older monks. The Chief Monk summons the Queen to pray for the dying monk to be reborn as her son. She makes an appeal before him and her invocation to Sumana Saamanera highlights his exemplary traits – spirituality, humaneness, and commitment to propagating Buddhist values. She extols his virtues, especially his strength which, in his case, is used to carry heavy bricks to build a temple. While she is in conversation with the Chief Priest outside the temple, a strong gust of wind followed by a freeze-frame, cinematically creates an atmosphere of mysticism, a symbolic enactment of the entry of Sumana Saamanera’s spirit into Vihara Mahadevi’s body which results in the birth of her son, Dutugemunu, overtly forging a nexus between Kingship and Buddhism.

Aloko Udapadi

Aloko Udapadi, directed by Chathra Weeraman and Baratha Gihan Hettiarachchi, was a big-budget film of approximately 130 million LKR. The film is set during the reign of King Walagamba when the kingdom is threatened by the invading South Indian group called Cholas. When the Cholas attack the palace, King Walagamba, Queen Soma, their two children, the Queen’s sister, and a senevi (soldier) make their escape in a cart. As they pass an ashram, the priest there alerts the Cholas saying “The great black Sinhalese is running away!” (Mahaa Kalu Sinhalayaa panala yanawo). As the cart is too heavy, Queen Soma jumps out and allows herself to be captured so that the King and the others can escape. The King arrives at a Buddhist ashram in the forest, where he offers the Chief Monk his Royal Seal and other important symbolic objects, imploring the Chief Monk to safeguard them. In the meantime, the film displays extremely inhuman attacks by the Cholas on innocent Sinhalese villagers. When the Chola forces are close to the King’s hiding place, he starts to think of rallying armies to defend himself, and by extension the Sinhala Buddhist nation. The catalyst for the King’s decision to rally forces is the massacre of Buddhist monks who were living in the forest. Only the Chief Monk and a few others who live in the hidden rocky mountainous area around the King are the survivors. The King starts to train the Sinhalese, and as the droughts arrive and more monks are killed, the remaining monks start to ponder what will become of the Dhamma- which until then was preserved exclusively via oral tradition, if all the monks are killed. Following the decisive battle between the Cholas and King Walagamba, the latter emerges victorious, and following this, at Aluwihare in Matale, the Buddhist monks start the movement to document the Tripitaka to preserve Buddhism in the world.

The Non-Buddhist “Other” as Malicious and Barbaric

Sri Lanka’s Post-war cinema industry engages in the re-telling of many historical stories of Sinhalese Kings who fight against foreign forces – many of whom appear to be non-Buddhist, barbaric Others.

In both films, the “enemy” is the Chola (South Indian Tamil) invaders positioned as the ‘Other’, contrasting them with the Sinhala-Buddhists, serving a political purpose alongside cinematic entertainment.

Hemachandra comments on the film saying that, “As in other historical movies, Aloko Udapadi has two black and white characters. The good character speaks Sinhala (the language of the Sinhala Buddhist), and the bad character speaks Tamil (the language of the invader). This illustrates that the good character represents the natives or in other words, Sinhala Buddhists and the bad character represents invaders or foreigners to the island of Sri Lanka. Interestingly, the bad character speaks Tamil, and it gives the meaning that Tamils do not belong to this island. This characterization supports the Sinhala Buddhist nationalist claim of the supremacy of Sinhala Buddhists in Sri Lanka” (rcssorg.blogspot.com/2017/03/aloko-udapadi- reconstructing-king.html).

The ‘black’ portrait of the Chola as ‘other’ can be seen in several instances throughout the films. They enact the Cholas mercilessly killing villagers, to get information about where the King is hiding. The bloodbath depicts the Cholas as brutal and unforgiving. Following this incident is a conversation between the Chola ranks which roughly translates as follows “Even at the cost of destroying all of the wealth of the Black Sinhalese, we must maintain our troops”, “If we create anarchy, the citizens will face hardships, and then they will betray the Black Sinhalese[2] and surrender him to us”.

It is at this point that the Cholas discuss that rumour that says the King is hiding in a temple. Soon after this discussion, the Chief Monk at the temple where the King is hiding returns to find that the place has been ransacked and that the two samaneras have been killed. The cinematic representation of this scene portrays the Cholas as barbaric killers who have no regard for the young age or the Buddhist affiliations of the two samaneras.

The massacre of the meditating Buddhist monks in the forest while the King is rallying forces against the Cholas – the images of the brutalised and savagely attacked corpses of Buddhist monks including samaneras, capture the Chola barbarism. The older monk’s positioning at the front, with the others helplessly behind him, eerily resonates with the Aranthalawa massacre of Buddhist monks by the LTTE.[3] The parallel between historic events and contemporary incidents of the civil war is a deliberate attempt to subliminally associate threats against the existing political system as threats against Buddhism.

The lawlessness and the brutality of the Cholas further position them as a group of non-Buddhist others whose goal is to obliterate the Sinhalese Buddhist nation. The Chola invasions are hence shown as a direct threat to Buddhism, subtly indicating that non-Buddhist others are always trying to sweep away the Buddhist legacy of the country. This, therefore, justifies the King’s actions to fight against the invading brutal forces of the Cholas. Hemachandra also comments on these depictions, saying that, “The constant reminder of violence against innocent civilians by the invader reminds the audience of the war between the Sri Lankan state and LTTE. For instance, the invader has been illustrated in the movie as a person who resorts to violence as a means of acquiring and maintaining power. The invader plunders the wealth of civilians and Buddhist monasteries and massacres innocent unarmed civilians and Buddhist monks” (rcssorg.blogspot.com/2017/03/aloko-udapadi- reconstructing-king.html).

This can be observed in the portrayal of the key characters in both Aloko Udapadi and Maharaja Gemunu. Through the use of skin tone and attire, a stark difference between the Sinhala-Buddhist King and the Chola leaders is configured. The former fashions civility, poise, and regality whereas the latter alludes to barbarity and lawlessness (see Fig. 1c, 1d, 1e, 2b, and 2c). In Fig. 1c. King Dutugemunu’s regal appearance is enhanced by his lighter skin tone and more modest attire. On the contrary, Fig. 1d portrays Elara – the Chola King as unshaved, dark-skinned, and, unlike Dutugemunu, Elara’s torso is bare, but adorned with ornate jewelry, significations of decadence and material wealth. In Fig.s 2b and 2c, the barbaric portrayal of the Chola leader with his murderous blade contrast with King Walagamba’s “humble”, yet civilized appearance. Demonisation of the “other” vis-a-vis physical attributes in both films further the black-and-white distinction between the non-Buddhist “Other” and the Sinhala-Buddhist leaders, invoking a historicised racist stereotype between the Sinhalese and the Tamils.

Both films rely on digital production and post-production technologies to heighten the cinematic effects of the scenes portraying the violence instigated by the non-Buddhist Other. Weeraman in an interview states that the pre-production of Aloko Udapaadi took 8 months as it was a process that involved multiple digital technologies, including the very first instance of using “Production Designing”, where the production designer “has to select the settings and thematic style to visually narrate the story” (vesess.com). In terms of casting actors to each role, the process has been predominantly digital. According to Weeraman, character sketches were drawn first, and then “all the sketches were digitized to decide on colour schemes for characters, and with the help of these digital illustrations, the production team began figuring out who to cast as the main characters” (ibid. emphasis added). The film has also used set extensions as a digital technique to construct the daunting battlements of the Cholas, as well as matte 3D paintings to add visual effects to many of the scenes of carnage. Both films use CGI (Computer-generated Imagery) to create visual effects of the invaders, the helpless Sinhalese villagers, and the scenes of combat. The post-production digital feeding of audio effects adds dramatic depth to the iconic scenes of both films.

The binary of Sinhala Buddhists as virtuous vs the malevolent Other as evil is further validated and given legitimacy by the intervention of the Buddhist clergy, who play dominant roles in the films. Both Dutugemunu and Walagamba defer to the advice of the Buddhist priests. Armed conflict is foregrounded as imperative for the protection of Buddhism, as inferred in the influence of the clergy.

The next section will interrogate how Aloko Udapadi and Maharaja Gemunu construct a historical validation for the continuous dialectic of state politics and religion.

The Intermingling of Religion and Politics

According to Priyath Liyanage, “Sinhalese politicians have often been calculating in their exploitation of the Buddhist card’, and the Sangha has been manipulated as much as they have been deferred to…When Buddhist leaders voice concerns that the faith is under threat, this is an extremely powerful and emotive message” (Liyanage 66). In Aloko Udapadi, King Walagamba hands over the Royal Seal and other important items to the Chief Monk for safekeeping. Throughout the film, the Chief Monk acts as the chief advisor to King Walagamba. These events align with the continued practice by the President as well as other Ministers of Sri Lanka to confer with the Sangha in conducting administrative work as well as during pivotal decision-making.

Towards the end of the first half of the film Godatta Thero – a young monk at the ashram informs the Chief Monk that he has decided to help the King organise an army. When the Chief Monk notes that such work is unsuitable for Monks, the young monk seeks blessings to give up his robes, thereby terminating his priesthood, in order to fight. Here, the Chief Monk’s idea that such violent involvement in war is not suitable for monks reverberates with the societal discourse that criticises the extent to which the Buddhist monks in Sri Lanka influence state politics. However, on the other hand, the young monk is cast in a heroic light. The Chief Monk’s acceptance of his decision to relieve himself of priesthood to fight alongside the King indicates the involvement Buddhist monks have had in Sri Lankan political history, and also can be read as a scene that places an almost “practical necessity” on the decision of monks to join the ruler to chase away the invaders. In contemporary discourse, it is this same “practical necessity” of times and situations that Buddhist monks use to intervene in state politics.

Perhaps the most critical point of the film is how the documentation of the Dhamma occurs as a direct result of the threats from as well as the vanquishing of the Other. Aloko Udapadi makes it clear that the documentation of the Dhamma could occur only because the King was able to dispel the non-Buddhist threats to the Maha Sangha. This nuanced event insinuates the interdependent relationship between religion and politics, fusing a hyphenated national identity of an exclusive Sinhala-Buddhist nation.

As Hemachandra points out “we have seen in the South Asian context, creating ‘one’ identity has left over other identities. The wave of historical movies in Sri Lanka including Aloko Udapadi illustrates this ‘oneness’ in its organic form… these movies have excluded non-Sinhala Buddhist communities as outsiders or foreigners who have been attempting to destroy the Sinhala Buddhist community, the native community of the island, since ancient times”(rcssorg.blogspot.com/2017/03/aloko-udapadi- reconstructing-king.html). Such depictions of the Sinhala Buddhist culture as one that is constantly under attack from non-Buddhist forces justify the need for Buddhist monks to remain present and vocal within the political arena. Though political power rests with the King, the spiritual and moral authority of the Buddhist clergy headed by the Sangharaja is reinforced not only through their physical and emotional proximity to the palace, but also through a transcendent relationship with Maharaja Gemunu. The trajectory that is followed legitimises violence, and war because it is waged not only in the name of Buddhism but to protect it from marauders, such as Elara, who threaten to destroy the Dhamma and its followers. The recurrent discourse in the film invests Dutugemunu with the role of savior, pitted against a “heathen’ king, creating resonances of a Sri Lankan version of the Crusades. The opening lines which are repeated thrice in the film encapsulate this:

I did not wage war because I am fond of seeing bloodshed; I did not wage war to prove that the strongest emerges as victorious; I waged war to save the dhamma for the sake of humanity. …. I wage war not to see blood, not to prove my strength, but I wage war to save the Dhamma.

This ideology is reiterated in the scene when Dutugemunu meets Nandimithra, the leader of the “giants” of his army of strongmen and their dialogue serves as a strategic transaction to explicate the contradictions of deploying violence to safeguard the precepts of Buddhism that proscribe any form of violence. Dutugemunu’s challenge to Nandimithra is:

Our dhamma does not allow us to harm even an ant. It does not allow us to harm even a person who comes to destroy the dhamma. Our dhamma is non-violent (innocent). This is why we give our lives to protect the dhamma. Harming these people, waging a war, moves us away from nirvana.

Nandimithra’s reply serves as the vindication for waging war: “We sacrifice our nirvana for that of the others”. This response construed as “selfless” elicits praise and admiration from Dutugamunu. This sentiment is paraphrased and repeated as a subliminal mechanism to inscribe the configuration of the King that is paralleled in popular discourses and historical texts.

Dutugemunu is acutely conscious of his commitment to upholding the Dhamma, even to the extent of invoking violence. King Devanampiyatissa, who is disinclined to engage in a military confrontation with Elara is perceived as a coward by his son. His father’s masculinity is challenged when he publicly humiliates him by presenting him with women’s jewelry. To escape his father’s wrath, but before he leaves the palace he writes a letter to his mother, persuasively presenting his rationale for doing so. Albeit transgressing the boundaries of acceptable behaviour, Dutugemunu makes a plea that has the potential to exonerate him because of the way in which he codifies his actions:

“If you cannot protect the dhamma for the sake of humanity if you cannot protect the kingdom for the sake of dhamma, what difference is there between these palace walls and I?”

By deploying this argument, the viewer’s emotions are aroused, precluding a judgement about the validity of using violence in the name of religion.

Religious intervention occurs between Dutugemunu and his brother, Tissa, whose ambition to be king prompts him to go to war with the former. But moments before they embark on the battle, as the two brothers stare at each other in tense silence, their confrontation is disrupted as a large procession of monks silently walk between the warring factions. Cinematically, this moment is rendered powerful through the long-shot frame which visually and auditorily captures the magnitude of religious authority. The film uses crowd multiplication as a digital technique to enhance the long procession of the monks, thereby visually creating a lasting impact on the audience. The scene positions the presence of Buddhist Monks as a magnanimous phenomenon in the conflict setting. The monks’ involvement delays the war for three days, allowing them time to provide Tissa refuge in the temple. Subsequently, the monks are also instrumental in enabling the brothers to reconcile by bringing Tissa to the palace and persuading Dutugemunu to forgive him.

Dutugemunu’s motivation to defeat Elara is underscored by his strict adherence to the Dhamma. His stature as a “good” king is assured by the respect he confers to the teaching of the Monks. His close association with them, framed by the continuous juxtaposition of images of the priests or temple with the palace and Queen Vihara Mahadevi and her sons, is in accordance with the concept of Dhammadvipa (the home of the Sinhala race and the seat of Theravada Buddhism) derived from the Mahavamsa and the Culavamsa (https://groundviews.org/2013/06/28/celluloid-nationalism-in-sri-lanka). The power structure of the Dhammadvipa consists of a union between the political authority of the king and the spiritual and moral authority of the Buddhist clergy headed by the Sangharaja.According to De Alwis, “In presenting political power and Buddhism to be indelibly linked, it implies that the preservation and advancement of the religion is a fundamental priority of the state. It also shows the Buddhist clergy to be not just an advisory, but also a participatory element in politics. The Sangharaja is an active figure in the royal court. While presenting the historically accurate close link between the Buddhist clergy and politics, the film goes further to suggest that Buddhism is the fundamental corrective force that guides political power” (https://groundviews.org/2013/06/28/celluloid-nationalism-in-sri-lanka).

These sentiments are echoed in Dutugamunu’s speech to his people prior to the battle with Elara thereby ensuring their endorsement: “The invader causes the unborn child to lose his dhamma. […] This exercise of mine is not to be King, but for the continuation of the Sambuddha Sasana.” The films’ foregrounding of the overarching influence of Buddhist clergy on the Kings’ decisions and the plot trajectory resonates with the continuing relationship between Buddhism and politics in contemporary Sri Lanka.

It is now an established fact that no President, Prime Minister, or Minister in Sri Lanka would take any significant decision without discussing it with the Malwathu and Asgiri Maha Viharas. Furthermore, when there are serious socio-political issues in the country creating civil unrest against the administration, the Maha Sangha standing for or against the citizens makes a significant impact on how the administration would handle such situations. The historical cinema’s construction of the concept of ruling under the advice and guidance of the Buddhist monks hence justifies the aforesaid contemporary practice. It allows the Buddhist monks to have political influence over the administration.

Conclusion

In both selected films, the Sinhalese-Buddhist heroic king is paralleled with former President Mahinda Rajapaksa. Amidst the political criticism directed at Mahinda Rajapaksa, the historical films keep the heroic narrative alive where the people are constantly reminded of what is seen as Rajapaksa’s critical leadership at a time of turmoil. Furthermore, the films enhance the liaisons between Buddhist monks and political leadership, alloying the relationship with historical tradition.

Even in the aftermath of bloody and prolonged ethnic conflict, the affirmation of monolithic ethnic identities continues to beleaguer post-war Sri Lanka. A close analysis of the narrative formulae of these plots of historical Sinhala films reveals that the configurations of ethnicity are problematically constructed. With the deeper entrenchment of Buddhism in dominant politics, the potential for the inclusion of minorities becomes even more untenable. In periods of exacerbated socio-political tension, identities become crucial. There is an anxiety to promote and safeguard specious notions of ethnic purity, which serve to validate ethnic violence. Dominant politics have been supported by Buddhist clergy, who exonerates political violence on the grounds that it serves to ensure the position of Buddhism in the country. Tambiah illustrates how monks were drawn into political violence—as perpetrators as well as victims—in the 1971 JVP insurrection and in the Sri Lankan Government’s war against the LTTE. He examines how the “sons of the Buddha” dedicated to nonviolence have transformed themselves into a militant, violent, “radical,” and political identity as “sons of the soil” which entails militant and violent politics and thus defies the non-violent teachings of Buddhism (Tambiah 95-96). When cinema serves as a form of escape from contending nationalist forces, the medium seeks solace in representations of an anachronistic or mythical utopia. In such a utopia, ethnic identities are fossilised into monolithic formations which do not offer any transforming potential. The utopias in Maharaja Gemunu and Aloko Udapadi constitute exclusive socio-political and religious spaces reserved for the Sinhala-Buddhist community, whilst discounting the ethno-religious ‘Other’.

[1] Dinidu Karunanayake’s seminal work on the post-war Sri Lankan film has also been integral to formulating the discussion in this essay.

[2] Throughout the film, Great Black Sinhalese or Black Sinhalese (i.e. Maha Kalu Sinhalaya) refers to the Sinhalese King.

[3] On the 2nd of June, 1987, Ven. Hegoda Sri Indasara Nayaka Thero and a group of young samaneras were ambushed and brutally massacred by the LTTE at Aranthalwa in the Ampara district. Only one samanera was able to save his life. Out of the 47 who had joined on a pilgrimage, 34, including 31 Buddhist monks were killed. Among the many incidents that drew wlrdwide attention to the atrocities committed by the LTTE, the Aranthalawa Massacre remains to be a pivotal moment were the international as well as local political attitudes towards the Eelam shifted.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Accelerating Higher Education Expansion and Development (AHEAD) Operation of the Ministry of Education funded by the World Bank.

References

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities. Verso Books, 2016.

Biyagamage, Hiyal. “Aloko Udapadi: The Making of an Epic.” Vesess, Vesess Pvt. Ltd., 22 Nov. 2016, https://www.vesess.com/aloko-udapadi/.

De Alwis, I. 2013. Celluloid Nationalism in Sri Lanka, Rev. of Siri Parakum. Groundviews. 28 Jun. https://groundviews.org/2013/06/28/celluloid-nationalism-in-sri-lanka/

D. H. Fleming. and Cheung, R., Cinemas, Identities and Beyond. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. 2009.

Dissanayake, Wimal. “Introduction. Nationhood, History, and Cinema: Reflections on the Asian Scene.” Colonialism and Nationalism in Asian Cinema, Wimal Dissanayake (ed.), 1994. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Dissanayake, Wimal. “Cinema, Nationhood, and Cultural Discourse in Sri Lanka.” Colonialism and Nationalism in Asian Cinema, Wimal Dissanayake (ed.), 1994. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Ethirajan, Anbarasan. “Sri Lanka Crisis: How War Heroes Became Villains.” BBC News, BBC, 12 May 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-61411532.

Hemachandra, Samal Vimukthi. “Aloko Udapadi: Reconstructing King Walagamba as President Mahinda Rajapaksa.” Aloko Udapadi: Reconstructing King Walagamba as President Mahinda Rajapaksa, Regional Centre for Strategic Studies, 15 Mar. 2017. http://rcssorg.blogspot.com/2017/03/aloko-udapadi- reconstructing-king.html.

Jayasinghe, Manouri and Dissanyake, Niluka “Post-Independence Sinhala Films: Milestones of Social Change in Sri Lanka in Asian Cinema, vol. 19, no. 2, 2008, pp. 35-45.

Karunanayake, Dinidu and Waradas, Thiyagaraja. What Lessons are We Talking About? Reconciliation and Memory in Post-Civil War Sri Lankan Cinema. Colombo: Karunaratne & Sons (Pvt.) Ltd, 2013. pp.1-18. Print.

Liyanage, Priyath. “Popular Buddhism, Politics and the Ethnic Problem.” Demanding Sacrifice: War and Negotiation in Sri Lanka, edited by Jeremy Armon and Liz Philipson, 4th ed., Conciliation Resources, London, 1998, pp. 65–69.

Naalir, M. (2010). Heralding a new era of Buddhism in Sri Lanka. Sunday Observer. 28/11/2010. http://archives.sundayobserver.lk/2010/11/28/fea07.asp

Rosenstone, Robert and Parvulescu, Constantin. eds., A Companion to the Historical Film. West Sussex: John Wiley and Sons, 2013. Print.

Silva, Neluka. The Gendered Nation: Contemporary Writing from South Asia, 2004. London and NY: Sage. Print.

Tambiah, Stanley, J. Buddhism Betrayed? Religion, Politics and Violence, 1992. Chicago & London: Chicago University Press.

Uyangoda, J. (1989). Cinema in Cultural and Political Debates in Sri Lanka. Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, 37, 37–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44111676

Williams, Alan. ed., Film and Nationalism. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2002. Print.